“What I was doing in the mountains was an adventure,” Saito recalls.“I was always an independent thinker. I repeated that practice, and it gave me the foundation to become an artist. You choose what to do.”

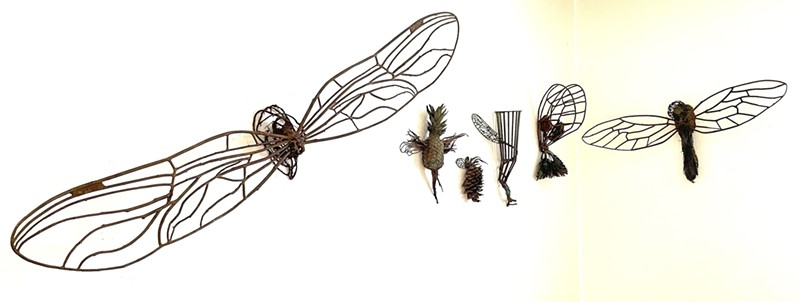

Saito’s road to becoming an artist took many twists and turns. Now he’s ready for new changes, with the announcement of Every Flying Insect Has a Fairy Spirit, his last show of cast-bronze sculpture at the William Havu Gallery.

Yoshitomo Saito, Every Flying Insect Has a Fairy Spirit, installation shot of bronze winged insect sculptures.

Yoshitomo Saito, William Havu Gallery

“After working and saving, I came to the Penland School of Craft in North Carolina,” Saito continues. “I set up enough money to stay one year studying. That was the original plan. But first I went to Miami to take an ESL course to learn English.”

After Penland, Saito headed west to the California College of Arts and Crafts studio glass program in Oakland. At CCAC, Saito met Fritz Dreisbach, a former assistant to Harvey Littleton, who recommended that he should study under another Littleton disciple, Marvin Lipofsky. Studio glass superstar Dale Chihuly was there, too. But after sampling art glass techniques, Saito's interest in the discipline diminished.

“I wanted to expand, to experiment in the field of sculpture, to create a pure contemporary art," Saito explains. "I needed to do something more."

CCAC had a foundry, and Saito then gravitated toward the equally difficult and dangerous field of bronze casting — or, put more simply, the act of melting and shaping metal. He was awed by its 5,000-year evolution from what was once “the highest technology a human being could use” to a medium still open to modern experimentation, and new ideas now in 2024.

“I was fascinated with the idea. I was looking for new materials and thinking about taking that direction after glass," he adds. “I thought I could use the highest technology from ancient work, and people will see me come up with something contemporary and dramatic.”

While New York remained the center of contemporary art, Saito surmises, “It was good to have something to go against. I wanted to do something else, to support diversity in art.” Saito stuck with it, earning his MFA in sculpture at CCAC.

“I'm a tenacious person, consistent,” he says. "Once I grab on, I don't give up easily. That led me to a teaching opportunity at the foundry. I was not so good at the work, but I was a really good teacher, and I wanted to seek this new way to survive as an independent artist.”

Saito’s bronze sculpture developed into a detailed, nature-derived platform, sparked by his experiences in the mountains as a young man. Many works, from woven circles of entwined branches to wall installations of multiple tiny pine cones or living detritus from the forest floor, developed over time. But he realized his chosen trade was expensive to uphold, from studio space roomy enough for bronze casting to the art materials and tools he used. Eventually, he found a more affordable place to work.

“I discovered Denver through my friends,” he notes. “I was buying bronze from a vendor in Denver, and I discovered that when you buy, you pay a lot for shipping. And studio rents here were so affordable. So I came here in 2006. It was the right timing, before the boom and bust; I got a house and a really expensive studio — but one that’s less expensive [than in California].”

Right off the bat, Saito was showing work in Denver at the esteemed Rule Gallery; in recent years, he’s been feted with splashy solo exhibitions at the Denver Botanic Gardens and the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. “Everything was waiting for me, but things changed after the recession,” he acknowledges. “It was a different picture. Still, I always got good reviews in local newspapers. Everything was rosy at the time. Nothing spectacular happened, but I’ve been happy.”

But he could never have foreseen what would come next. On New Year’s Eve in 2021, Saito climbed a ten-foot ladder in order to repair some messy branches on a tree in his yard. He lost his balance and fell to the ground, cracking three vertebrae and landing in a prolonged hospital stay for surgery and complications that followed. After coming home, he wanted to resume his work, but learned that was not so easy to do.

Nearly three years later, Saito expresses regret: “After my injury, casting bronze was no longer possible for me, physically. And similar to glasswork, casting bronze is so dangerous, so expensive. Stopping casting to do my concept of bronze sculpture, doing everything myself, is not something attractive to me now.”

With these words, Saito will present his last show at the Havu Gallery, where he’s been a gallery artist most recently. He'll be sharing wall space with his fellow artist and friend Heidi Jung, and the exhibitions run through August 17.

But is it over for Saito after the show? Not at all, he says, although he’ll give up his big studio and donate the leftover works he stores there.

“My skill in welding is top-notch as a technical art,” he says. “I can still make very intricate work, and I can still weld in small scale. But I need time to seek a new theme and a new body of work.”

His newest works in the exhibition revisit the insect world that delighted him as a boy, hinting at what’s next.

“I grew up in insect-loving culture. During summer vacation, I very often went to a park, field or forest to chase insects,” Saito remembers. “We kids all did it: We caught cicadas, dragonflies and lightning bugs to bring home and see how weird they looked. Those things came back to me after the accident as the inspiration for a new series.”

Like the jazz music he’s loved for decades, Saito’s work ethic happens in the moment. “I have never dried up with ideas. Making art for me is more of a hands, eyes, brain, body, physical experience," he says.

“In the future, I will do something I've never done," Saito concludes. "I live with the moment of making it.”

Yoshitomo Saito, Every Flying Insect Has a Fairy Spirit: Friday, June 28, through July 17, William Havu Gallery, 1040 Cherokee Street. Opening Reception: Friday, June 28, 5 to 8 p.m. Learn more about Yoshitomo Saito here.