In Colorado, the rate of people returning to homelessness has increased each year since 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In 2022, the rate of people across the Denver metro area who returned to homelessness after six months off the street was 9 percent — up from 6 percent in 2019 — and more than 20 percent had returned after two years off the street, more than in any year since 2018.

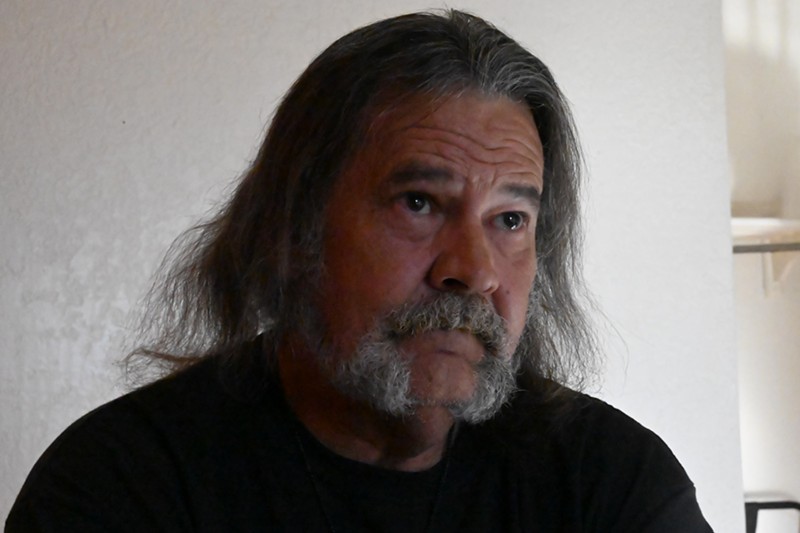

Lifelong Denver resident Joe Henry thought he had a way out of homelessness when he landed a gig at the Brown Palace, but bad luck and mistaken judgment led him back to square one.

When Henry found his roommate dead in her room last October, he didn't know her death would lead him to homelessness and a life of sleeping in his car and empty spaces and out-of-order rooms in the Brown Palace hotel.

Henry had bought a white-noise machine for his roommate a few weeks earlier, he says, and heard it humming from her room nonstop for a day and a half, prompting him to check on her. She was addicted to crack, according to Henry, but he thinks fentanyl may have had to do with why she was on the ground, blue and rigid, when he found her.

"When I found her on the ground, she was ice cold," he says. "She and I were pretty tight."

Henry's roommate helped pay the rent, and he couldn't afford it alone. After a few days, his landlord asked him to leave the small two-bedroom house in Lakewood so he could bring in two new tenants.

Henry had a job as a custodian at Lasley Elementary School in Lakewood and his dead roommate's ’97 Subaru Legacy. After leaving their apartment, he drove to an empty O'Reilly's Auto Parts parking lot near West Alameda Avenue and South Federal Boulevard in Denver, and slept in the car. On weekends he had enough money to rent a motel room for three days, where he would shower and sleep before returning to the streets.

When Henry wasn't working, he was drinking. Even though working around the kids at Lasley cheered him up, he didn't like his job as a custodian, mopping floors and plunging toilets. But he's loved fixing things since he was a kid.

"I was homeless, and it was becoming too damn difficult to work," he says. "And that job just wasn't me. I fix shit. That's just what I do."

Around Halloween, Henry says, he left his custodian job and was living on the streets full-time. His drinking increased, and when he was down to his last few bucks, he decided to join Step Denver, a residential substance abuse recovery program that he'd heard about a few years earlier while listening to Peter Boyles, a local radio host.

Henry started living at Step Denver at 2029 Larimer Street after Thanksgiving and began working on getting sober and returning to a job in maintenance. He moved his car to a downtown pay lot that never charged him or towed him while it was parked it there for a month and a half. Things were finally looking up.

"I had some stability," he says. "For the first couple weeks, you're not doing a lot, but at least I had a place to stay. They provide you with a little bit of food. So I had that, and as soon as I could, I started pounding out résumés. "

After a month with Step Denver, he was hired for a maintenance position with the Brown Palace that paid $21 an hour. After living most of his life in Denver. Henry considers the Brown Palace "an icon" of the city. "Presidents have stayed there," he likes to note.

"The Palace, to me, was like the perfect job," he says. "I felt like the man of the hour. They needed somebody who can fix and understand the older, manual technology."

Henry still considers the Brown Palace "an icon" of the city. "Presidents have stayed there," he likes to note.

Bennito L. Kelty

"When people checked in or had a problem in their room, I was the guy to go fix the heat or whatever their problem. It could be anything, because that place is falling apart," he says.

Duties included unclogging drains, tightening loose toilet paper holders and fixing the heating and cooling in rooms, which was the most common issue. He frequently went to the top rooms to respond to complaints about the lack of hot water, a problem caused by the hotel's boilers being on the bottom floor and water taking so long to travel up; all he had to do was tell guests to run the water for ten to fifteen minutes.

"I adored doing room calls. I was really good at them," he recalls. "I put out a lot of fires in those rooms with hot, pissed-off people, and I would get them smoothed over. I'd explain, 'I'll do what I can do here, but you've got to remember you're in a 135-year-old building.'"

Part of Henry's job was also doing major repairs on rooms that were out of order and couldn't sell. One such room had "a hole in the wall where we had to get to the plumbing," he says.

Shortly after he started at the Brown Palace, Henry lost his housing with Step Denver. He says he was kicked out after missing an appointment, and he went back to living in his car. Step Denver isn't able to comment on Henry's time there because of privacy reasons, according to Stephanie Landree, the administration director for the group.

Henry says he lived in his car for nearly four months, through "the most brutal part of winter," before it was stolen with everything he owned inside. "So I was homeless and working at the Brown Palace."

He slept out on the streets a couple of nights, but on an especially cold night in April, he went back to the Brown Palace and fell asleep in a chair on the tenth floor. The floor used to be an upholstery, woodworking and paint shop for the hotel but is used more as a storage area now, according to Henry.

"It was cold, cold, and I had lost everything. I had no winter clothes," Henry says. "I had nowhere else to go."

As the hotel's handyman, Henry "pretty much had access to the whole building." At first he continued sleeping in the tenth-floor chair. When his shift ended in the afternoons, he would pretend to go home, even saying goodbye to his co-workers.

"I would play it off: 'Hey, I'm going home, got to catch that bus, see you tomorrow,'" he recalls. "And so I'd hit the streets until 7 or 8 at night and then come back. I know how to get around the building without being seen."

Henry would spend the rest of his night on the tenth floor among boxes and spare furniture. In the morning, he would descend for a shower in an out-of-order room in the Brown Palace or in the adjoining Holiday Inn Express, a sister hotel attached with a sky bridge.

"Then I started thinking, 'Shit, why am I going down to one of them out-of-orders in the morning?'" Henry says. "Why don't I just sneak down to one of them at 11 o'clock at night and just sleep in there?"

For about three months, from the spring into summer, Henry lived in out-of-order rooms at the Brown Palace. He wasn't spending every night there. "I spent many a night on the street still," he notes, but admits to coming into the Brown Palace to sleep, shower or do laundry on most nights.

Henry was caught on August 7, when a security guard noticed him crossing the sky bridge. The guard quickly realized that Henry was off to stay in an out-of-order room, and told management.

"He's not stupid," Henry says.

The Brown Palace fired Henry on August 8. He was back at square one, with no car but more money in his pocket this time. He rented a room at Motel 6 in Lakewood, and spent most of the money he had saved from his Brown Palace paychecks to extend his stay two days at a time, for a week and a half. Henry says he feels stuck in a hole, unable to climb out.

"It is impossible," he says. "What else am I going to do? At my age, I really don't see another life."

He thought his job at the Brown Palace was his break and his ticket out of homelessness. But on Monday, August 19, he ran out of money to keep staying at the motel.

"I blew the last of my money," he says. "I'm on the street now."

The Brown Palace did not respond to requests for comment.