“That was the biggest issue facing the city,” Johnston says. “People had given up thinking that it was fixable.”

In March 2023, candidate Johnston told Westword he was running to "end unsheltered homelessness." It was a tall order: The most recent Point in Time count, a federally funded tally of homeless residents, reported that the City and County of Denver was home to 1,300 unsheltered homeless individuals that January, in addition to roughly 4,000 in shelters. And that didn't count the migrants who'd started flooding the city in December 2022, prompting then-Mayor Michael Hancock to declare a state of emergency.

Johnston's focus on homelessness pushed him into the runoff, and he won the election in June 2023. By the time he was inaugurated on July 17, he was ready to put our money where his mouth was. Here's a chronological look at what he did...and where that money went:

Mayor Mike Johnston announces his plan to bring 1,000 homeless people indoors before the end of the calendar year.

Bennito L. Kelty

July 2023

The day after he's inaugurated, Johnston declares homelessness an emergency, which allows him to speed up "the procurement of critical services," he notes in his declaration. He also announces the start of House1000, an initiative to house 1,000 homeless residents in Denver before the end of the year.

Two days later, he appoints Cole Chandler to a newly created position: senior advisor on homelessness resolution. After founding the Colorado Village Collaborative, which pioneered the idea of tiny homes and Safe Outdoor Spaces in Denver, Chandler had moved to a position as state director of homelessness initiatives with the Colorado Department of Human Services. He's there less than a year when Johnston brings him back to Denver for a big job and a big salary: $160,000.

For House1000, Johnston plans to rely on hotels converted into shelters as well as ten micro-communities spread throughout the city that will be similar to the safe spaces Chandler tested with the CVC. The new mayor rolls out this plan at a town hall in the Five Points neighborhood on July 26, the first in a series that he promises to hold in all of Denver's 78 official neighborhoods. At this gathering, Johnston tells residents concerned about the growing number of encampments in the city that he will not sweep them unless it is a public health or safety emergency.

The next day, the Denver Housing Authority agrees to buy the 194-room Best Western Central Park hotel at 4595 Quebec Street for $26 million and then lease it to the city starting in September.

August

On August 2, Johnston authorizes his first sweep of a homeless encampment. Two days later, the city clears an encampment at 22nd and Stout streets over concerns regarding a rat infestation; Johnston cites "public health and safety" reasons for sweeping the camp, but the city has no housing ready to offer those who are displaced. A week later, the city purchases the Stay Inn at 12033 East 38th for $9 million with the intention of turning it into a homeless shelter with a micro-community in front. Johnston soon begins the bidding process for service providers to run micro-communities.

On August 24, Johnston approves a second sweep, this time of an encampment at East 17th Avenue and Logan Street. Public safety after a shooting earlier in the week is the justification, though the city still doesn't have housing ready to offer the encampment's residents.

But the next day, Johnston shares a map of ten micro-communities and one hotel, the Best Western purchased a month earlier. The mayor says he'd tried to distribute the micro-communities equitably, but residents and councilmembers challenge this, pointing out that most of the sites are in poorer neighborhoods. Still, Johnston insists that the city has been "intentional about making sure we have an equitable map" and that the distribution of sites "represents all regions." Denver City Council approves the purchase of 200 pallet units, a type of shed-like housing unit for micro-communities, for $7 million; most of the proposed micro-communities have a capacity ranging from twenty to sixty units.

September

On September 12, Johnston reveals that his budget for House1000 will be about $50 million for the rest of 2023. Included in that budget are $20 million for micro-communities and $24 million for converting hotels into shelters; $19 million of that is set aside to renovate the Best Western Central Park. Another $4 million is earmarked for leasing units for people leaving temporary shelter, and $5 million is dedicated to services for mental health and workforce development. About $750,000 is set aside to perform sweeps.

Johnston says he's relying on the $250 million 2023-2024 budget for the Department of Housing Stability to cover his housing plan. A week later, Denver City Council approves the transfer of $8 million saved by the city for its COVID response to a HOST fund supporting Johnston's House1000 efforts. On September 22, Laura Brudzynski, executive director of HOST, leaves her position after nine months to become the chief operating officer at Archway Communities, one of Denver's oldest nonprofit affordable-housing developers.

On September 26, Johnston approves the sweep of an encampment near the Governor's Mansion at Eighth Avenue and Logan Street. This is the first Johnston-authorized sweep that leads to homeless residents moving indoors: It sends 83 homeless residents to the newly converted Best Western Central Park. Several dozen individuals say they were never offered housing, however.

After residents of the Golden Triangle Creative District see that their community is slated to host two micro-communities, the district holds a community meeting without the mayor; on September 28, Johnston finally meets with members of the group. The Golden Triangle residents aren't alone in their worries: People who live in a pocket of Holly Hills are eyeing becoming a registered neighborhood in order to push back against plans by Johnston to put a micro-community at 5500 East Yale Avenue.

Meanwhile, the Overland neighborhood is battling the idea of hosting what's slated to be the largest micro-community, with 155 units and more than 200 residents. "This particular site is huge," Overland resident Helene Orr tells Westword. "It's a big problem, it's a tough issue, and for it to be successful, there has to be some neighborhood buy-in, and [Johnston] is really getting off on a bad foot."

October

On October 8, Johnston meets with residents of the Overland neighborhood and tells them that their micro-community will be the first to begin construction. After heated discussion, Chandler says the city has agreed to reduce the site's size to 120 units. On October 12, Johnston meets with Golden Triangle residents again, and they repeat their concerns about hosting two micro-communities in a small area. Four days later, Johnston cancels plans for a 32-unit micro-community in the neighborhood, citing "additional complexities" with planning.

On October 14, the Housekeys Action Network Denver, a local advocacy group, denounces Johnston's ongoing use of sweeps to clear encampments, noting that even though the mayor only authorized two sweeps, city agencies continued to carry out soft sweeps or right-of-way enforcements. That night, Johnston meets with residents and business owners in Montbello to discuss plans for a micro-community in Central Park. The mayor says he plans to build a 54-unit micro-community and convert the 96-unit Stay Inn to a non-congregate shelter.

Mayor Mike Johnston held a meeting with the residents of the Overland neighborhood in October to tell them about his plans for a micro-community there.

Bennito L. Kelty

"This includes close coordination with partners including service providers, Denver Housing Authority, the Veterans Administration, the State of Colorado and others involved in the process to help us expedite the process to move people into housing."

In mid-October, Denver starts "pre-construction activities," mostly excavation, for micro-communities at four sites: Overland, the Golden Triangle, Baker and Central Park. On October 30, council approves a $6 million contract with Clayton Properties to provide the city with 300 manufactured sleeping units, or MSUs.

The next day, Johnston approves the sweep of an encampment near 21st and Curtis streets, where the largest homeless encampment in the city wraps around an entire block.

November

On November 2, Johnston tells Holly Hills residents that he has canceled plans to build a micro-community at 5500 East Yale Avenue; residents say they are "thrilled." Six days later, the mayor's office confirms that property owners with the Krisana Group have pulled out of a deal to provide land for a micro-community in Virginia Village. Seven micro-community sites remain out of the original ten planned.

In the meantime, Denver City Council approves a one-year, $1.3 million lease for the DoubleTree Hotel at 4040 Quebec Street, with the intention of using it as a non-congregate shelter for 300 people and a cold-weather congregate shelter for another 150 people; council also approves a $10 million option to buy the hotel for $43 million.

On November 10, Johnston announces a partnership with Housing Connector, a nonprofit tech company based in Seattle, to provide residents in House1000 sites with listings of apartments that take housing vouchers so that they can have long-term housing options.

Denver Police officers talk during an encampment sweep in front of the Governor's Mansion on September 26.

Bennito L. Kelty

The next day, Johnston authorizes another sweep, this one located in the Ballpark District near 24th and Arapahoe streets; 21 people are moved indoors.

On November 20, the city council picks Bayaud Enterprises to run the micro-community in Central Park, in front of the Stay Inn, with a one-year, $2.3 million contract. But two days later, Councilwoman Stacie Gilmore resigns as head of the Safety & Housing Committee, concerned that Johnston has been using the emergency declaration to push through contracts for hotels and micro-communities without enough committee input.

On November 27, Denver taps the Salvation Army to manage the DoubleTree Hotel and its 450 beds after council approves a one-year, $10 million contract. But three days later, Johnston cancels a micro-community site at 5000 Tower Road in Green Valley Ranch because it is "not economically viable due to costs to develop the land."

Six of the ten sites remain.

December

With a month to go and 700 people still to move indoors in order to meet his goal, Johnston's office begins poaching employees from other departments to work on the House1000 effort.

But on December 4, Johnston cancels two more micro-community sites: the one planned for a parking lot at 1498 Irving Street, next to the Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales Branch Library, and another at 3700 Galapago Street, in the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood. Four sites remain, all delayed from their original scheduled openings. Meanwhile, Denver City Council approves a $1.5 million, one-year contract with the Gathering Place to have the service provider run the Elati Village micro-community. It also passes a $2.2 million, one-year contract to hire the CVC to run the largest micro-community, but on the condition that it install only sixty units at the site for the first six months. Council also approves a $4.3 million, year-long contract with Satellite Shelters to provide the city's micro-communities with up to fourteen community centers where homeless residents can eat, cook and do laundry, among other chores.

On December 7, Johnston authorizes his largest sweep, clearing more than 150 people out of a camp at 21st and Curtis streets. Nearly all of these residents move into the DoubleTree, pushing the House1000 tally from 350 to 500, the halfway mark. Five days later, the city sweeps an encampment at East 48th Avenue and Colorado Boulevard, moving 102 more people indoors.

On December 16, residents of the Hampden neighborhood pack a meeting with Johnston, who shares plans for the Tamarac Family Shelter, a former Embassy Suites at 7525 East Hampden Avenue that will be converted into a non-congregate site for 200 homeless families. Two days later, city council approves a three-month lease for the 205 rooms at $825,000 a month. The contract comes with an option to buy the hotel for $21 million in March.

Council also approves a one-year, $10 million lease with Central Lodging to use a Radisson at 4849 Bannock Street as a shelter for 220 people, and okays a $2 million contract with Bayaud Enterprises to run the Radisson. It also approves a $3 million contract with the St. Francis Center to run the Comfort Inn at 4685 Quebec Street, which HOST has been using since January as a 136-unit non-congregate shelter. A $1.7 million contract with the Salvation Army to offer three meals a day at all of the city's micro-communities also sails through council.

On December 19, Johnston returns to the Ballpark District for another sweep near 20th and Champa streets that moves nearly 100 people indoors. The next day, he sweeps everyone left at the encampment at 22nd and Stout streets. On December 21, a sweep at East 18th Avenue and Marion Street moves 64 more people indoors.

On December 28, move-in day for the Tamarac Family Shelter welcomes several dozen homeless families referred by shelters and service providers. The House1000 tally hits 950 people housed.

On December 31, Johnston sweeps homeless residents living near Arkins Court and the South Platte River, and also opens the city's first micro-community: the Stay Inn Micro-Community outside of the hotel in Central Park. With that, he declares his House1000 mission a success — even though not all of those 1,000 residents were fully housed by federal and local standards, which require fourteen consecutive days of being indoors.

January

Migrants take center stage. On January 1, migrants and their supporters march on the Capitol to stop a planned sweep of a migrant encampment that has been growing for several months outside the Quality Inn at 2601 Zuni Street, now a migrant shelter. But on January 3, the city does conduct a sweep there. Two days later, the city issues a cold-weather emergency and activates additional shelter space to get homeless residents and migrants off the streets; it had previously extended the length of time migrants were able to stay in shelters.

On January 11, anticipating more cold weather, the city sweeps a migrant encampment on West 48th Avenue and Fox Street, moving about 100 people into shelters. The next day, the number of migrants living in city-operated shelters in Denver surpasses the 5,000 mark for the first time.

On January 20, though, the city ends a fifteen-day cold-weather emergency during which it brought more than 3,200 migrants and local homeless residents inside. While most homeless residents return to the streets, the suspended length-of-stay policy allows migrants to continue staying in shelters.

At the end of the month, Denver City Council approves the No Freezing Sweeps bill, banning city agencies from performing sweeps when the weather is below 32 degrees outside. Craig Arfsten, founder of Citizens for a Safe and Clean Denver, also wins an appeal with the Denver Board of Adjustments over the CVC micro-community, which delays the opening and forces Johnston to resubmit permit requests.

Homeless residents at an encampment in the Ballpark District prepare to board a bus that will take them to transitional housing.

Bennito L. Kelty

On February 2, Johnston vetoes the No Freezing Sweeps bill. And as the weather warms up, the city resumes discharging migrants — as many as 300 a week. Meanwhile, Johnston announces that the city will reduce DMV and recreation center hours and make other cuts to cover its response to the migrant crisis, estimated at $180 million for the year. Mid-month, Johnston introduces the position of Newcomer Program Director to lead his migrant response; immigration lawyer Sarah Plastino is hired at $175,000 a year.

Having housed 1,000 individuals in 2023, Johnston rebrands his House1000 campaign as All In Mile High, with a goal of moving another 1,000 people indoors by the end of 2024. And in the meantime, he announces plans to close four migrant shelters in order to save the city $60 million.

March

On March 4, the CVC opens La Paz, the largest micro-community in the city, at 621 West Wesley Avenue.

A week later, Johnston resumes sweeping as part of his homelessness resolution plan, clearing about 100 people at West Colfax Avenue and Umatilla Street. While the city says they went to La Paz, the CVC later reports that only about thirty to forty people came from the sweep.

On March 16, two people are shot dead at the DoubleTree Hotel; no arrests have been made. Denver's homeless residents name the place "MurderTree Hotel." Meanwhile, transgender and female homeless residents begin moving into Elati Village.

On March 26, council approves a $2 million, one-year contract with the Denver Basic Income Project, which pays homeless residents a no-strings-attached guaranteed income, to continue the program into 2025. Two days later, the city closes a migrant encampment outside Elitch Gardens after the amusement park requests the clearance before opening day. About fifty migrants are taken to a congregate shelter at a church, but some return to the street; others move to a hidden encampment in Central Park.

April

No fooling: On the first day of April, the city closes two of the four migrant shelters it had planned to shutter on February 28. Two days later, the city closes a third, leaving only a single migrant shelter open: the Quality Inn. Ten days later, Johnston reveals a new budget plan that allows the city to restore DMV and recreation center hours along with other previously cut services. In the process, he also cuts internal hiring budgets, mostly for police and firefighters.

The mayor makes cuts to migrant services as well, including reducing the city's length-of-stay policy from a three-week to a 72-hour maximum. On the same day, two city employees arrive in El Paso with the mission of updating migrants about the shortened stay at Denver shelters. The goal is to deter migrants from thinking about coming here on those free buses provided in Texas.

Residents asked Mayor Mike Johnston for more lighting and fencing while they deal with increased homelessness and drug use in their neighborhoods.

Bennito L. Kelty

The next day, Johnston releases a "Newcomer Playbook" that tells other cities how they can shelter, feed and transport migrants the way Denver did. In response, Congresswoman Lauren Boebert tweets that "our nation is being stolen."

May

On May 8, the city clears the migrant encampment that's been under an overpass in Central Park for over a month; most residents go to a congregate shelter. Others try to set up another encampment but are soon swept.

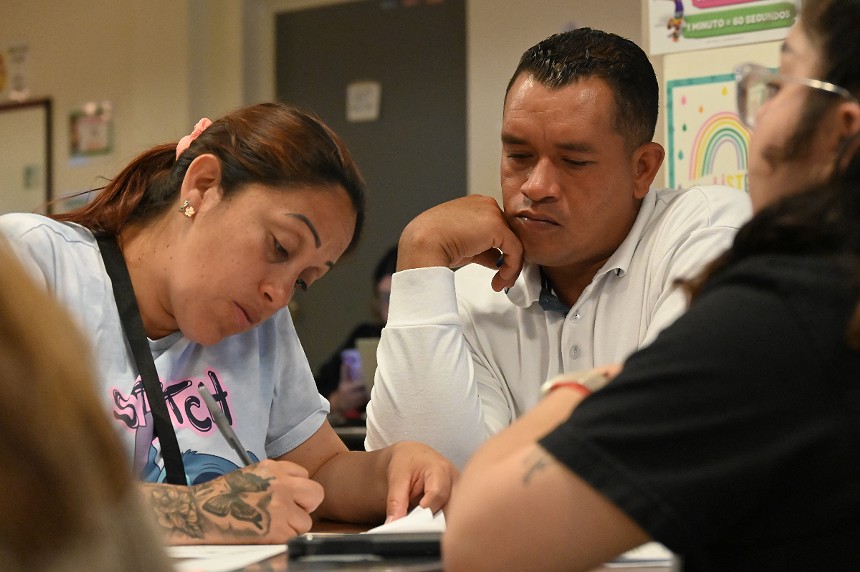

Meanwhile, on May 9, the city launches the Denver Asylum Seekers Program and begins paying six months' rent for more than 800 migrants while they go through the process of applying for asylum to earn their work permits.Two weeks later, Chandler unveils a new idea for the mayor's homelessness resolution plan, proposing a $5 million contract with Housing Connector to test putting people directly into leased units. He tells the council's Safety & Housing Committee it will "skip the expensive interim step" of using micro-communities and hotels.

On May 23, Denver City Council delivers a letter to Johnston telling him temporary housing in micro-communities and hotels "is not enough," and that he has to come up with "appropriate" programs and services to "prevent displacement" long-term.

Rony Blanco and Yenire Cirilo sign the paperwork to join the Denver Asylum Seekers Program.

Bennito L. Kelty

With only an estimated 52 homeless veterans living in Denver by Johnston's count, the mayor says he plans to house all of them and end veteran homelessness in the city by the end of 2024. Also on June 2, Denver City Council approves increasing its security spending from $400,000 to $3.4 million at homeless and migrant shelters.

Two days later, the city briefs council regarding plans to keep a pair of Denver staffers in El Paso, to discourage migrants from coming to the Mile High City. Meanwhile, 350 migrants who are in the Asylum Seekers Program enter the WorkReady program, which offers job training and credentialing.

On June 16, Jamie Rife, the former head of the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative who became director of HOST in January, gives council a project cost of Johnston's homelessness plan from the time he took office to the end of 2024: $155 million. From July 18, 2023 to May 9, the city spent $56 million addressing homelessness, according to the city, including $49 million on one-time costs like contracts with hotels and micro-community site preparation. The city still needs $84 million to get through 2024, and after that Denver will require about $58 million a year to continue resolving homelessness, Rife says.

On June 25, Johnston discusses House1000, All in Mile High and the Denver Asylum Seekers Program at the International Conference on Homelessness in Paris. Five days later, Denver closes the last hotel it was operating as a migrant shelter, the Quality Inn. From now on, migrants arriving in the city will be put in non-congregate shelters, either in a church or renovated warehouse.

Meanwhile, on June 28, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that local governments have the right to sweep homeless residents who are sleeping outside. Denver vows not to change its protocol.

July 2024

“I’m very proud of our first year,” Johnston says. “Look back to a year ago, when people couldn’t get out of hospitals because they were ringed with encampments.”

According to the city, over the past twelve months more than 1,800 people have been moved indoors through Johnston's All In Mile High and House1000 initiatives. Although close to 200 of them have left, more than 500 of the people who were housed through those programs are now in permanent housing.

More than 1,200 people housed by Johnston are still in micro-communities or hotels: 158 in micro-communities and the rest in hotels. The city is still leasing and operating five hotels as homeless shelters; it has yet to start moving anybody into the Stay Inn. "We are working to identify a partner necessary to provide supportive housing as soon as possible at this site," says city spokesman Ewing. "Once completed, this property will serve as a permanent housing resource for persons experiencing sheltered and unsheltered homelessness in Denver."

Staff at La Paz Micro-Community in South Denver reports early success with most homeless residents, but it's still a long road to housing and getting surrounding homeowners on board.

Bennito L. Kelty

As for the 500-plus shed-like units that council approved for micro-communities, so far the city has only purchased and installed 54 pallet shelters, 104 MSUs and four community buildings.

The number of migrants arriving from the southern border has dropped in recent weeks, since President Joe Biden issued an executive order that bans migrants from gaining asylum if they cross the border illegally, and allows border officials to turn more migrants away at the border. The city says this is contributing to the drop, as is the success of the city staffers in El Paso.

When Johnston took office, more than 13,000 migrants had already arrived in Denver since Hancock declared an emergency in December 2022; the city had spent more than $21 million supporting them with shelter, food and transportation to other cities. During Johnston's administration, more than 29,000 migrants have arrived, and the city has spent more than $51 million supporting them.

“Migrants were obviously not something we can control, but I think we found a way to make it work,” Johnston says. “As of today, we have them all in housing or shelter and on a path to work. We did it all without having to cut public services in an ongoing way.”