November 29, 1864

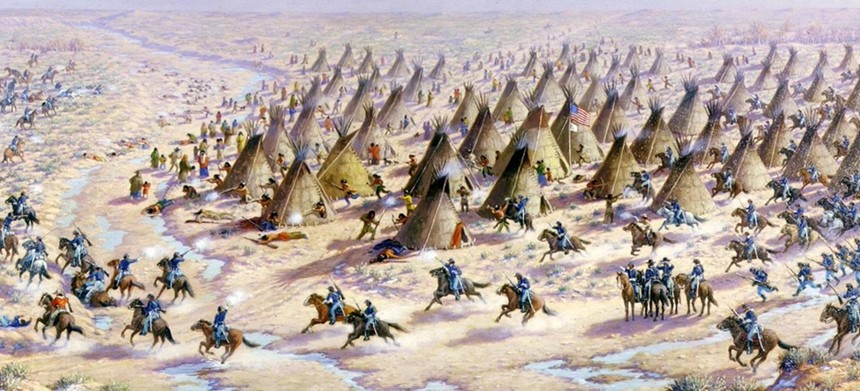

At dawn on November 29, 1864, Colonel John Chivington led more than 600 volunteers and troops with the First and Third Colorado Regiments on a violent raid of a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho camped along the banks of the Big Sandy, 173 miles southeast of the five-year-old boomtown of Denver. Having just requested a meeting with Territorial Governor John Evans and consulted with the U.S. Army, Cheyenne chief Black Kettle believed that the camp was protected, and was flying the white flag.But now an estimated 230 tribal members were slaughtered — women, children, elderly men and close to twenty chiefs, including White Antelope, who sang the Cheyenne death song: “Nothing lives long...only the earth and the mountains.”

Black Kettle escaped, grievously injured, and he and other survivors headed up creek beds in the cold, looking for safety. They finally found it far away from Colorado, on the Northern Cheyenne reservation in Montana, the Northern Arapaho reservation in Wyoming, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho reservation in Oklahoma.

Meanwhile, soldiers mutilated the bodies and took their plunder — promised by the recruitment fliers for the 100-day volunteer cavalry posted that August — back to Denver, where their trophies were displayed at the Denver Theater’s holiday show.

April 28, 2012

When the $110 million History Colorado Center opened at 1200 Broadway on April 28, 2012, the David Tryba-designed building boasted many marvels, including a huge terrazzo map of the state as it would look from 400 miles up in space, inlaid in the floor of the giant atrium; newfangled, steampunk-y time machines were designed to roll over the map, telling certain parts of the Colorado story.But they did not hint at one scandalous story unfolding a floor above, where History Colorado (formerly the Colorado Historical Society) had installed state-of-the-art core exhibits, dubbed “Colorado Stories,” that focused on different industries — skiing (complete with a virtual-reality jump), mining (ride a shaky elevator into the depth of the Earth!) — and communities. There was a replica of a trading room at Bent’s Old Fort, another of barracks at the Camp Amache Japanese-American internment camp, and a display devoted to Lincoln Hills, a last resort for vacationing Black Coloradans that had opened in Gilpin County in 1922, when they weren’t allowed at most vacation retreats. There were some quibbles about these exhibits — stereotypical caricatures of the Natives visiting Bent’s Fort (which were later eliminated), a layout that made the Amache barracks look like a nice overnight camp (the wide aisles were designed to make the space accessible, as a notice posted later by the door acknowledged). But accurately capturing the past is no easy task, even when it’s done right.

Through a narrow entrance on this second floor was another core exhibit, Collision: The Sand Creek Massacre, 1860s-Today, that went very wrong. A sign by the entrance noted that it might not be suitable for children, despite the fact that the other Disneyfied exhibits were clearly designed to appeal to kids.

But Collision was dedicated to one of the cruelest, darkest chapters of Colorado’s history, noted that sign: the “unprovoked attack” at Sand Creek. “A congressional commission concluded the massacre was ‘foul, dastardly and cruel,’” it added. Lives weren’t the only things lost that day, though.

“Something larger was lost after Sand Creek: the chance for peace,” the Collision sign continued. “The massacre intensified anger and mistrust among American Indian residents and those settlers who wanted to take their lands, hardening the divisions between competing nations. A generation of warfare ensued throughout the West, claiming many more victims.”

The battle for truth would come later.

November 7, 2000

Colorado never forgot the Sand Creek Massacre, though how the story was told took many turns.After not one, but two congressional investigations, as well as an Army probe, Evans was disgraced, and he had to resign as territorial governor. But after he helped bring a railroad to town, he was later recognized as one of the city’s most civic-minded citizens. He had a mountain named after him in the 1890s, as well as a Denver street that runs right past the University of Denver, which he’d co-founded with Chivington, a fellow Methodist minister, just months before the massacre.

On July 24, 1909, the Colorado Pioneers Association dedicated a Civil War Monument installed just below the west steps of the Colorado Capitol. Below the figure of a soldier designed by Captain Jack Howland, a member of the First Colorado Cavalry, was a list of all the Civil War “battles and engagements” that Coloradans had fought in, including “The Battle of Sand Creek.”

A monument with the same label was put by the actual site of the massacre in 1950, twenty-plus miles from Eads and just past the ghost town of Chivington. (The colonel almost had a Denver street named after him, too, but it became Hale Parkway instead.)

But what happened at Sand Creek was no Civil War battle, and by the 1990s, there was a move to erase the words on the statue. Working with legislators and Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal descendants of the massacre, then-state historian David Halaas came up with a solution that would not erase history, but explain it. A plaque was put just below the statue, telling what really happened at Sand Creek and noting that “the controversy surrounding the Civil War Monument has become a symbol of Coloradans’ struggle to understand and take responsibility for our past.”

At the time, Halaas and others were struggling with another challenge: having the actual massacre site declared a national monument. With Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, the only American Indian in Congress, leading the charge — and after some last-second drama that involved Halaas’s discovery of letters written by Captain Silas Soule to Colonel Edward Wynkoop, telling of the horrible things he’d seen that day at Sand Creek, activities he’d refused to allow his troops to join — the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Establishment Act of 2000 was signed into law on November 7, 2000.

With the law came numerous provisions, including calling for the Department of the Interior, through the National Park Service, to create a vision for the site as well as official protocols for consulting with the tribes every step of the way. “The development of the general management plan included an extensive consultation process involving members of the National Park Service and the designated Sand Creek representatives of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, the Colorado state historic preservation officer and staff of History Colorado (formerly the Colorado Historical Society), and representatives of Kiowa County,” where the massacre site is located, a draft report on the process noted.

By the time the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site was officially dedicated in April 2007, there had been many consultations with the three tribes, consultations that the NPS has continued to this day. They’d met every year at the start of the Sand Creek Massacre Spiritual Healing Run, a tradition started in 1999 that took members of the tribes on a run to Denver after they gathered at the site to remember their ancestors.

But when History Colorado began planning the exhibits for its new building, it ignored that road map, federal dictates be damned.

On December 5, 2011, with the opening of the History Colorado Center less than six months away, Cheyenne leader Joe Fox sent History Colorado officials a letter reminding them of this: “History Colorado, along with the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, Northern Arapaho Tribe, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma, and the Park Service are by federal legislation recognized as partners in the development and management of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. ... Any exhibit on the tragic events of November 29, 1864, which is produced by History Colorado, we fear, will appear to carry the endorsement of all the partners, including the Northern Cheyenne Tribe. Unfortunately, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe was not consulted until late November, just months before the exhibit is scheduled to open.”

Then-state historian Bill Convery went to a meeting with the tribes in Billings that month. In his doctoral dissertation, “Colorado Stories: Interpreting Colorado History for Public Audiences at the History Colorado Center,” he recalled that the meeting was “bruising,” as “consultants from all three tribes expressed their deep sense of personal pain, insult, and outrage at History Colorado’s interpretation, and requested a formal apology from the lead developer and the institution’s CEO.”

They didn’t get it. Instead, exhibit planners made some slight changes to Collision, corrected a few outright mistakes, and scheduled another meeting with the tribes in March 2012, when the Northern Cheyenne asked that the exhibit’s opening be postponed.

History Colorado declined, and when the History Colorado Center opened on April 28, Collision opened, too.

The tribes were not happy. Collision was still filled with “errors and omissions,” Fox wrote History Colorado director Ed Nichols that August. “Others reveal shabby research and a shocking lack of curatorial understanding of the massacre, the events surrounding it, and its meaning to history.” On behalf of the tribe, he again “respectfully” requested that Collision be closed and that History Colorado “schedule meaningful consultation meetings with the tribes so that we may work together to produce an exhibit that properly interprets Sand Creek and its profound meaning to our tribes, the nation and the world.”

Again, History Colorado refused.

For nearly a year after Collision opened, the tribal descendants worked behind the scenes, trying to get History Colorado to close the exhibit until it could do enough research to get the story right.

The tribes didn’t need to do any research. They knew the story. They’d lived the story. It was their story.

February 14, 2013

Having heard about the descendants’ concerns, I had gone through Collision several times, experiencing the cheesy you-are-there sound effects, seeing the artifacts they said History Colorado did not have permission to show, hearing why this was no inevitable collision, but the result of colonization and conquest. The name added insult to horrific injury.“Collision? It’s a massacre,” Norma Gorneau, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Sand Creek Massacre Descendants Committee who’d learned about the massacre from her great-grandmother, told me. “They’re not even trying to meet us halfway. We had asked them specifically to at least make some corrections. We asked them to take it down because it’s supposed to be entertaining for them, but for us it’s a major incident that was done to us...a major tragedy done to us...and they want to minimize it. When they said that they weren’t going to take it down, it brought up a bunch of angry feelings.”

Finally, the descendants were angry enough to allow me to tell their story. I published the first piece in February 2013, ten months after the exhibit had opened. And five months later, it was closed, never to reopen. History Colorado agreed to work on a new exhibit dedicated to the Indigenous inhabitants of the region...after doing the proper consultations.

“The important thing is to talk about its meaning, to show the horror of Sand Creek and why it affected the tribes so much, and how it impacted the relationship between the tribes and the government,” said Halaas, the former state historian, who didn’t live to see that exhibit completed. “If History Colorado wants to be the sentinel of Colorado history, they have to get it right.”

And finally, they have.

While History Colorado was slowly getting it right, others were paying attention to the tribal descendants, too.

In March 2014, then-Governor John Hickenlooper — who’d studied the history of Colonel Wynkoop when he was an unemployed geologist deciding what to name the brewery he was opening on Wynkoop Street — appointed a Sand Creek Massacre 150th Anniversary Commission, to guide a proper commemoration of the heinous event. At the conclusion of that year’s healing run, Hickenlooper stood on the steps of the Colorado Capitol, right by the Civil War Monument, and told how Chief White Antelope had stood his ground that day in 1864 and sung the death song: “Nothing lives long...only the earth and the mountains.”He read from Soule’s letters, he talked about the congressional investigations and spoke of the “deep moral failure” of John Evans. “We should not be afraid to criticize and condemn,” he said. And then, “on behalf of the State of Colorado,” he apologized to the tribes.

And Hickenlooper went further. He worked with the legislators and the Department of Higher Education, which oversees History Colorado, to come up with a new structure that cut the board from 34 to nine and would hold those boardmembers accountable for an organization whose budget was even more out of control than its bad publicity. In August 2015, the new board was in...and the director of History Colorado was out, as was the COO who’d been in charge of all the opening exhibits.

A new group took over at History Colorado, one that slowly, carefully, respectfully worked to mend relationships with the tribal descendants and move the consultations along. Shannon Voirol was the project director and worked with Sam Bock, the lead exhibit developer, and a dedicated staff; they were supported not just by a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, but by Jason Hanson, the chief creative officer who’d come on after Hickenlooper overhauled History Colorado, as well as director Steve Turner (promoted from state preservation officer) and then Dawn DePrince, who took over after Turner moved on.

More action continued at the Capitol, too. A proposal to create a true Sand Creek Massacre monument was proposed, then fast-tracked. During the George Floyd protests, when the Civil War figure was toppled, a committee of legislators decided that spot would be appropriate for the Sand Creek memorial, looking out over the land where the tribes were once at home.

In August 2021, Governor Jared Polis rescinded the two 1864 proclamations issued by Evans that had led to Sand Creek. The first directed “friendly Indians” to gather at specific camps and threatened those who did not comply. The second ordered citizens to “kill and destroy...hostile Indians” and urged them to “take captive, and hold to their own private use and benefit, all property of said hostile Indians that they may capture, and receive all stolen property recovered from said Indians such reward as may be deemed proper and just therefore.”

“We can’t change the past, but we can honor the memories of those we lost by recognizing their sacrifice and to do better,” Polis explained.

History Colorado continued to do better, too. Under the new leadership, many of the staffers took tours of the Sand Creek Massacre site, to see how the NPS had gotten it right. The core group working on the exhibit went to the three reservations that the tribal descendants called home, talking to the elders, experiencing their ways of life, and going over every possible detail of the exhibit that would not only replace Collision, but go so much further. It would share the history of these people from long before colonization. It would put their lives in context. It would be in their own words — two versions, one for the Cheyenne, one for the Arapaho. And the words would be available in their own languages.

November 19, 2022

Ten days before the 158th anniversary of the Sand Creek Massacre, on November 19, 2022, History Colorado held a special ceremony to mark the opening of its new exhibit, The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal That Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever. It began, as all official state events have for the past two years, with a land acknowledgment recognizing the Indigenous people who lived on this land now known as Colorado.Then traditional songs and speeches filled the atrium, where two tipis stand on the map where the time machines never worked.

The day before, the entire History Colorado Center had been closed while tribal descendants and other Indigenous people were able to tour the exhibit at their own pace, reading the words that had been approved, and often written, by their own representatives.

“We are some of Colorado’s original land keepers, and our link to this place is at the heart of our Arapaho culture,” begins the Arapaho version. “Even though our ancestors were violently forced to leave after the Sand Creek Massacre, we are still connected to Colorado.”

“Before the Sand Creek Massacre, the wealth of our economy, the fierceness of our protectors, and the power of our traditions made us some of the strongest people of the plains,” says the Cheyenne version. “But the Sand Creek Massacre changed everything. Today, we work to maintain our traditions, our language, and our connection with the land.”

The two parallel narratives take the stories of the tribes through the founding of “The Illegal City of Denver” and the “Discarded Treaties and Broken Promises” to a visit to the White House made by Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders in 1863. And then their stories converge in a segment on the Sand Creek Massacre as understated as Collision was over the top. But in its simplicity, it is far more terrifying. It is real.

There’s more, much more, to the exhibit, which lets viewers choose their own direction from this point — to a quiet contemplation area that re-creates dawn on the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site with the understated sound of birds, to a display where you can read the letters of Silas Soule, to a theater where you can choose from dozens of oral histories.

Near the end, in “We Are Still Here,” each tribe has a display case filled with items that show their lives today, from COVID masks to football helmets of those rare high school teams that have actually asked the tribes if they can use their names for school mascots. Norma Gorneau is so pleased with the outcome of the exhibit that she loaned it a ceremonial dress.

Some of the exhibit is open-ended. History Colorado is now studying the Indian boarding schools discussed on one panel: “Our people’s traditions were often beaten out of the children, beginning the very moment they arrived at the schools.” There are photos of the Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run, which wasn’t held this year for the first time in more than two decades, partly so that tribal members could attend the exhibit opening. And in October, the Department of the Interior doubled the size of the national site, which will require more planning and consultations.

And still the story continues. Two days before the exhibit opened, the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board, which had been established by Polis to consider replacing offensive place names, had taken a surprise vote and agreed to change the name of Mount Evans to Mount Blue Sky, pending the approval of the governor and the feds. That idea had first been proposed two years ago with the support of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma.

But it does not have the support of the Northern Cheyenne, who point out that Blue Sky is a name for the Arapaho people; the Cheyenne use it as part of a secret, sacred ceremony and do not believe it is an appropriate name for the mountain. At the opening ceremony, one Cheynne leader told me that while the new exhibit gets the story right, the renaming of Mount Evans could be headed in another wrong direction. Once again, they feel like they were not really consulted, not truly heard.

Around the corner from the atrium where the opening ceremony was held stands the Civil War Monument soldier, still covered with paint from the protests, on temporary display until he goes to a new home. But plans to put a Sand Creek Memorial in his spot have gotten mired in discussions over design, and what the piece should really represent.

Nothing lives long...only the earth and the mountains.

No matter what they are called.